On

Good Cat In Screenland by

Richard Cohen

Since the past has ceased to throw its light on the future, the mind of man wanders in obscurity

— Alexis de Tocqueville

The beauty of narrative is that any story is full of other stories. That’s what Good Cat in Screenland is — full of stories. Or should I have said the beauty of narrative is that it’s not essentially linear, not unless you really straighten it out, but then that would be no way to make sense of the events. The point is to make sense of them, but to do that you have to work out how to tell them.

Los Angeles, at least for someone who’s never been there, can seem like a fantasy city of movie locations shuffled around in fictional worlds. The idea of a ‘Los Angeles itself’ almost sounds like a contradiction in terms. In fact Los Angeles itself is sometimes described as a shuffle of locations rather than a textbook city with a ‘proper’ centre. Good Cat In Screenland, like Richard Cohen’s other films, is set in the geography and society of this ‘Los Angeles itself’. The films are about the urban communities and politics of Los Angeles. They are rooted in urban, social, political and architectural locations.

Culver City is one of those Los Angeles locations. It sprung up as an early twentieth century development of real estate and movie studios in western Los Angeles. The City’s motto is ‘The Heart of Screenland’: It flourished in the movie boom, perhaps declined a bit along with the big studios, and by the late 1990s it looks like it must have been ready for an injection of capital, for resurgence and redevelopment. Good Cat In Screenland starts with a Chinese capitalist, Abraham Hu, riding into town.

Washington and Culver Boulevards cross at a sharp angle, like a pair of chopsticks. The Culver Hotel is held in the narrow triangle between them. It’s shaped like a slice of pie. It looks like a confection with a crimped, corbelled crust. It’s filled with show business history. John Wayne once won it gambling. After an opening shot of eucalypts on a hillside above the city, we have a long shot of the hotel standing above the skyline. Seen side-on from a distance it looks like a doll’s house or a movie set with nothing behind it.

The shot zooms straight in to start exploring the film’s slice through contemporary history. We quickly realise the hotel is at the cross roads of stories, of lives, of cultures, of countries, of places and of people in transition. Everything is in transition. Maybe any slice at a particular place at a particular time will reveal other places and other times. That’s the way we conceive history these days. But there is a lot of past here and it complicates things, scarcely throwing any light on the future. There are stories about China’s Cultural Revolution and then its capitalist revolution, about copper mining in Chile, about the Wizard of Oz and the shenanigans of the Munchkins, and about raw Chinese capitalism surging across the Pacific to encounter the middle kingdom of American capitalism.

Good Cat’s framing story is about the ownership and management of the hotel. It begins when Abraham buys the bankrupt hotel in the late 1990s. The filmmaker Richard Cohen first met Abraham back then. He leased a room in the hotel as an office. When he suggests to Abraham that the price of the hotel might have been $2m, Abraham corrects him. $3m he says, and a good investment. Like so many details this is ambiguous. It’s talking about money; it’s hard to tell exactly whether Abraham is being honest or boasting or discrete or polite, or all of them. Anyway, ambiguous or not, honest or not, it’s just one of those details in a great narrative pile of them that the film and the viewer has to take in and make sense of.

Then comes Joseph Guo who buys into a partnership with Abraham. Both owners have a business background peculiar to Chinese of their generation. Veterans of Mao’s China and the Cultural Revolution they now practice capitalism like it’s a kind of human nature they were always waiting to express. Joseph lives in the hotel with his wife Wendy, managing it while Abraham is off on other business ventures, like copper mining in Chile. This style of reborn capitalism with its resource mining, manufacture and multinational investment is a bit different from that of the American microcosm they’ve landed in though. Hotel management is service capitalism and demands a sense of the local cultural subtleties. Hotels scarcely existed in Mao’s China, let alone show business hotels. And although Joseph and Wendy try to get the feel of the hotel by trying out rooms on all the floors, the local culture comes with its own kind of inscrutable, mandarin system of consultants, restaurateurs, and service contractors, and it’s complicated by the culture of local developers and urban politics, all playing on their home ground, all more or less frustrating Joseph’s progress. Then there’s the hotel itself, enriched but complicated by nearly a century of show business history. And there are these filmmakers there too, interviewing, capturing events, people, and moments, Richard Cohen documenting he-could-not-have-known-what.

I say the film is about Joseph Guo and Abraham Hu, but Abraham is mostly absent, off screen somewhere doing serious business. In fact most of the film happens before he reappears, and when he does we hardly see him. He installs his son, Hu Xiang, a new generation capitalist communist. While Joseph is out of the hotel, the lawyers arrive, and like a band of powerful, unannounced knights they claim ownership of the shaky Camelot for Abraham. When Joseph returns, it’s all he can do to fight his way back in, and when he does, all he can do is set up his own camp. So we have two opposing claimants, camped in the heart of the hotel, battling to control it. Joseph has been paying off his share in the hotel, maybe he has already paid it off, but there are legalities: documents, conversations, interpretations. In a way it’s just one more challenge for Joseph — Good Cat has already been a series of trials and jousts all the way through — but this is like the ultimate challenge.

Like all the trials, the dispute over ownership will be ambiguous. It’s an uncertain world; we don’t really have all the facts. We just get claim and counterclaim. There is no commanding voice-over. All the way through Good Cat our sympathies just seem to have to align themselves.

In other films that Richard Cohen has made it’s a bit different. Taylor’s Campaign is about Ron Taylor who runs for local office as an advocate of the homeless in Santa Monica. You can’t help but side with Ron and the homeless. Even though it’s a gentle and unobtrusive style of filmmaking, and maybe Ron and the homeless have some rough edges, you know that is the intention. With the gentleness goes the tenderness for the people in the film. That’s how the film’s made, that’s the way the story’s told, right up to Ron, a couple of years after the events and his hair grown long, reflecting on how grateful he is not to have been elected. Going to School: Ir a La Escuela is even clearer. You can’t feel anything but tenderness for the kids and their parents struggling to get an education system that works with their disabilities — not when two kids smile with affection at each other, or extend their hands to each other, or when a mother is radiant and gentle in her pursuit of fairness. It’s full of love and grace.

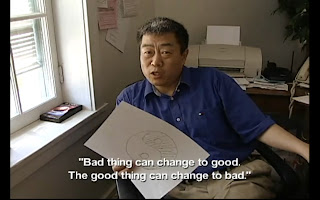

Good Cat though is a kind of ‘bigger’ history: the people have more money and resources; there’s the back-story of world capitalism. Set in the Culver Hotel, it’s much more a revelation of events of ‘show business’ proportions. The events happen over a longer time and they are ambiguous. Like the other films though Good Cat just gently shows us the events — or that’s what it seems like — and because of that or despite that it’s all more unclear. You have to form your judgments of Joseph, whose predicaments dominate the film, for yourself. Reading over this essay nothing was more obvious to me than that I made too many judgements of Joseph; the film makes none. Joseph quotes Deng Xiaoping’s revisionist take on capitalism versus socialism: if the cat gets the mouse it’s a good cat. Joseph may be a good cat but maybe he might not get the mouse, not here where he finds himself in Screenland.

The Munchkins stayed in the hotel when the Wizard of Oz was being made. In fact when Joseph in one of his trials earlier in the film takes on a campaign to keep local parking space for the hotel, not only does he enter the whole world of urban development politics, but he does so like Dorothy, with one of the surviving Munchkin’s at his side. The material of Cohen’s films is serious. The strain on Joseph’s face often shows, but while the telling is understated, the world itself isn’t. Joseph takes up the Munchkin theme as a hotel attraction, he wonders about real yellow bricks or painting bricks yellow. None of this is exactly funny, except it’s shown like you’ve got to smile. Tenderly. Especially for Joseph who for all his energy and sincerity finds it hard to get on top of urban development or hotel management Culver City style. At one stage Joseph installs various ‘creative people’ on a floor in the hotel, but most of the local players that Joseph has to work with in order to make the hotel work never quite seem to fill you with confidence or hope. They are more like errant than shining knights. Joseph struggles, lurches between trust and suspicion, yet somehow makes the troubles that beset him seem unwarranted. Several of his partners and allies — whether through his misjudgement or inexperience, or whether through their own failings — don’t quite seem to match Joseph’s own besieged virtues. He doesn’t strut or lord it. Rather, playing the role of the man with the biggest burdens is the same as playing the role of the man with the biggest vision. It’s a role he partly makes for himself and partly finds himself in. History and events can do that to anyone.

Joseph’s vision of course may be sometimes a bit flawed. In the dispute with developers and the City over the parking, maybe Joseph expects too much. He wants the car-park kept next door for his guests. And even though the building of the new cinema complex begins with the sacrifice of a big beautiful tree, maybe cinema seats and urban redevelopment have more social or democratic value than public parking spaces for Joseph’s paying guests. And when Joseph decides to develop a restaurant in the hotel and call it ‘Munchkins’, maybe that’s not quite as grand as Abraham’s earlier vision of getting a ‘world class’ Chinese chef, especially when ‘Munchkins’ pretty much goes wrong. Or at least, no one involved seems too happy with it.

So far as Good Cat is about the meeting of cultural styles, the clash of the two capitalisms has a kind of gentle reflection in the meeting of the different types of music being made in the film. Joseph on Chinese violin and Wendy on Chinese mandolin bring their own kind of beauty with them, right from the start. It is like a refuge from the headaches of business. There are American musicians too passing through the hotel. The Jazz Bakery is a nearby venue. Indeed during the post-9/11 tourist slump, musicians seem to be almost the only guests. The saxophonist Lou Donaldson tells a little story about wanting to be a baseball player, back in the time of segregation. Just a little story like this seems to be important for the film that Good Cat is — even the bit about a ballpark being named after the musican back where he grew up in North Carolina. It’s another ingredient in the filling, like an American counterpoint to the Cultural Revolution. At one stage I think there was some bluegrass-sounding music being played on Chinese instruments — unless I was imagining it, which is sort of possible. Good Cat is a kind of hallucinatory experience, but not because the filmmaking isn’t true to reality, anything but. It’s because it’s sort of incredibly true. This is what the world is like: an harassed Chinese businessmen, schooled in the Cultural Revolution, playing traditional music with his wife in a Hotel haunted by show business, above a restaurant named after the ‘Munchkins’. And it’s all so tenderly witnessed and retold

Not only is Good Cat about ‘bigger history’ than Richard Cohen’s other films, in its own way it’s more intimate. Perhaps that is why the events are rendered with less of a guiding, political judgement. Narrative style is not so much about formalities, it’s about the ethics of content. And in documentary so much depends on getting this right. On a couple of occasions in Taylor’s Campaign people say things would have happened differently if the camera hadn’t been filming them — otherwise a local property owner or local police might not have acted so reasonably with the homeless people squatting on the footpath. In Good Cat there is no mention of this kind of ‘filmmakers’ presence’. Yet the filmmakers are always present in Good Cat. At one stage Julie Moody, an interior designer working for Joseph, has a difference with him about her fee — a fee that Joseph is unwilling to pay. It seems though that she doesn’t give up on Joseph; as she says, she invited him to give her a hug, and he did. And later, when the two camps are warring over the ownership she addresses the filmmaker: ‘Richard, you and I are the only one’s left’. You are aware of the filmmakers in Good Cat — someone has to be somewhere pretty close to all this to get it on film — but never by some kind of obtrusive self-reference, or obtrusive voice-over. Nor by the sort of obtrusive absence that plays as objectivity. The filmmaker is there in the film’s content as fellow citizen, resident, acquaintance and friend, as unobtrusive, sympathetic witness. It’s about the filmmaker’s experience too. The events asked to be lived or witnessed, and then if possible, somehow retold.

That’s the thing about

Good Cat in Screenland: the way it’s told, its narrative richness. Events are unscripted and the art of the film consists in the way they are put together. The events are filmed over a number of years, and all the people bring different stories and different histories with them, and the filmmaker has to work with the events filmed. And then the events filmed are often events about other events — people reporting, telling or remembering things. And the events range from world historical to utterly mundane, and there is usually more than one interpretation. The narrative material in

Good Cat is just so hard to handle. Just trying to describe elements of the plot of

Good Cat In Screenland I’ve realised how difficult the material is. I’ve mostly written about Joseph, but it’s not just about Joseph. Looking at the film a second time it was still full of surprises. To understand the events is not only a matter of the attitude we are to take to them and the sympathies we feel; it’s a matter of how to order the events. I don’t mean it’s a matter of straightening out the chronology, I mean it’s a matter of giving the events the illumination of plot. It is quite a feat of narrative engineering; it succeeds as a labour of love.

On a number of occasions Joseph makes some philosophical reflections. He quotes Tao wisdom, and Mao, and Deng. Nearly always it’s with a kind of sense of the inadequacy of these things. They have their value but only as the wisdom of the past and not so much for forging the path to the future. When he’s struggling Joseph finds he has to fall back on the precepts of ‘image’ and ‘reputation’, and during his most difficult battles with staff and contractors all he can cite is ‘Reduce costs! That’s management!’ As it is for Joseph coming to terms with his experiences, telling these events on film seems like a matter of finding a way through. The beauty of Good Cat is that it manages to use events from different times to illuminate one another. This is the achievement of the writing and editing. It manages to do two things: it shows what is almost the objective obscurity of these events, at least for those who wander through them; but with its own kind of tender, narrative determination it leads us through, it manages to gather some light from the past to throw on the future.